The contents of this article are for information and educational purposes only. Patriot Propaganda does not officially recommend using any of the tactics, techniques or procedures presented.

***

A minute’s success pays the failure of years. ROBERT BROWNING

MOVING THROUGH THE STAGES of the Art Activist Process Model is not always easy in practice. This is where creative practice comes in. Let’s save ourselves some trouble and cover the common mistakes made by practitioners who resolve to implement the AAPM in their own art activism campaigns.

Research sometimes feels like a formality. For those of us who have been working as artists and activists for years, we have a pretty good idea of what’s at stake and what can be done. We know what we know. But we don’t know what we don’t know.

Think about it this way: most of us know our own neighborhoods pretty well, but what do we really know? The tneighbours we’re friendly with, the places we like to go, the paths we usually take. There’s a lot, however, we miss. What about the new family down the block? The auto body shop in the alley? The utility tunnels under the sidewalks?

When we operate solely from our own experiences, interests, perspectives, and comforts, we miss a lot. It takes self-awareness and humility to admit that we don’t know it all and have to seek out more information.

Research can draw you in like a warm blanket. It’s a cozy place. The stages in the AAPM that come after research bring us closer to action, which entails a lot more risk, so collecting more (and more) information can feel safer than moving forward. And since it’s hard to know when we’ve done enough research, the temptation is always to do more.

There’s always more community members to reach out to, more books in the library, and more tools and techniques to experiment with, but at some point enough is enough and it’s time to move on. If, later, we realize we haven’t done enough research, we can always come back.

Sketching requires experimentation and exploration, but sometimes, in our hurry to move on and “Do It!” we rush through the sketch process by grasping at the first sign of success. One workable idea is enough, so why bother with more, especially when so many of them are bad?

Well, because more ideas give us more to choose from, to combine, and to work with. As the philosopher Émile Chartier once said, “Nothing is more dangerous than an idea, when it’s the only one we have.”

Like over-emphasizing research, over-emphasizing sketches can feel very comfortable. An endless refrain of “what if we did this?” can be both fun and safe. Among activists, this tendency shows itself when, after the reports and data are in, we hold an almost endless series of strategy meetings. In an art context, it happens when the artist falls madly in love with the act of creating: pushing clay around but never finishing a sculpture. There’s a time to stop futzing around and move on.

Lack of evaluation happens when we’re sick and tired of working on the project and just want to get it done. It can happen when we are too excited and can’t wait to make it happen. Or sometimes we are so invested in one outcome, or so buried in the process, that we lose perspective. But without an honest, thorough evaluation, plans can fall apart. Sometimes we’re afraid to be critical because we don’t want to hurt others we are working with. If someone is excited about an idea from the sketch phase, offering criticism can be awkward. It’s even worse when this conflict isn’t between you and someone else, but you and yourself. But criticism is necessary to give and receive. Remind yourself that evaluation is what makes the project stronger.

We’ve all been in situations where a new member of a group makes a smart suggestion only to have it quickly shot down before it gets off the ground, often by someone jumping in with comments like, “Yeah, we tried that once back in 2004 and I can tell you, it is not going to work.” The person giving this kind of criticism often thinks they are being helpful: offering a reminder of complex realities, or protecting the project from being released into the world before it’s ready, but it also stunts creativity. We all fear the embarrassment of letting an idea into the world before it is ready, and this makes us more likely to be excessively critical and allow few ideas, if any, through the evaluation stage. Giving criticism that is productive, generative, and keeps people motivated may be the trickiest skill to master, even for the most experienced creative people, but with practice it becomes easier.

The point of the process is an outcome. Developing a project is a lot of fun, but seeing it through to completion takes hard work. It demands late nights and long hours, and heavy lifting of all kinds. The work usually doesn’t go as planned: materials are hard to find, things break, people get sick, target locations shift, and police presence increases. These changes and setbacks happen in every project. Not accounting for the amount of work needed and the delays that inevitably occur can be depressing and debilitating. Producing good work takes a lot of work: we need to know and expect this.

Often, pieces are pressured by political deadlines. Or, participants may be frustrated with a lack of results and press the group toward action. There are many reasons to push production at the expense of other stages. But all the elements of the creative process need to be well balanced for the final product to be any good. Creativity needs time and space; rushing the process to the final project is a recipe for an uncreative action.

And finally,

Besides placing the wrong emphasis on a certain stage, another common mistake in the creative process is putting stages in the wrong order. We often see folks take on the Critic role too early, evaluating while they are still researching. Or they contaminate their artistic sketches with critical comments, like “This is terrible”, or “I have no talent.” Others don’t evaluate until after they have pushed through the production stage: putting days of hard work into a project, only to stand back for the first time once it is done to see how they could have improved it.

When the stages are done out of order, we risk truncating the creative brainstorming necessary for innovative ideas, or putting half-baked ideas out into the world where they are bound to fail. We can move back and forth between the stages: a sketch that failed the evaluation stage needs to go back to research and sketching, before moving forward again. But even as we move back and forth, the stages of the process are meant to be followed in their sequential order. Walt Disney, with no shortage of money, created multiple rooms for each stage of his creative practice. As he and his team moved from one stage to the next, they would literally move into another room designed and decorated for that purpose. Building three additional rooms onto your apartment or studio may not be an option for you, but finding ways to silo each stage and giving it a distinct and clear time and place certainly is.

Working in a group can make the problem of sequence either better or worse. Different people have different strengths and weaknesses. There’s the person who loves to think up wacky ideas but never follows through on them. Or the overly critical member who finds fault in everything. If we let our critical comrade play too large a role in the research and sketch process, or put our friend with the fecund imagination in charge of production, we are asking for trouble. But as a collective we can recognize each other’s skills and arrange the expertise of our group so our talents can complement instead of undermine one another’s.

WE ALREADY MENTIONED the need to “turn down the pressure” on yourself when discussing the creative habitat, but we also want to discuss a related problem that is so pervasive and so crippling to the creative process that it warrants its own section. This is the problem of perfection.

Perfection is the voice that creeps up while you’re working on a project and whispers over your shoulder, “that could be a little bit better.” It sounds like the voice of a friendly coach, so you listen. You keep reworking and polishing, and your piece does get a little bit better, in smaller and smaller increments. There’s some movement toward this quest for an ideal, and it feels important — until you realize hours, days, or weeks have passed and you haven’t actually completed anything. Sure, we owe it to the causes we are working on to always strive to do our best, but we also have to ask ourselves: What best serves the cause? And what cause are we actually serving? Within the world of art there’s all kinds of myths and distortions around perfection and craft. In our idealized perceptions of artists, we often position them as magical people who make things perfectly the first time, or if not the first time, inevitably through their relentless pursuit of perfection. These myths of perfection and commitment are lauded, way past the point when they are helpful or even healthy.

Such was the case with Jay DeFeo, a Beat-era painter in San Francisco. DeFeo started working on a painting called The Rose in 1958. When she started, the painting was nine feet tall; it eventually grew to eleven-and-a-half feet tall and seven-and-a-half feet wide. DeFeo worked on it in her apartment, adding layers of paint and reworking it, for eight years. In 1966, the painting weighed close to two thousand pounds and had eleven inches of paint on its surface. She was made to call it quits —for the time being—when she was evicted from her apartment, and her painting was so large and so heavy that movers had to carve out a two foot section of the wall below her window so that it could be removed with a crane.

The Rose was moved to the Pasadena Museum that year, but DeFeo was still not done. She got a key to the museum so she could continue working on the painting adding “final touches” at all hours. The story of The Rose was told with reverence to art students as an exemplar of an artist with incredible commitment to her work; an artist in search of perfection. What wasn’t mentioned in the aspirational tale of Jay DeFeo was that, at the end of that eight years of painting, her career had lost its momentum, her health and marriage were in poor shape, and she was depressed and drinking. Yes, DeFeo was committed to The Rose, but the commitment was misallocated. She had lost perspective.

Let’s look at a counter example: the Kingsmen. Even if you don’t know the band you’ve probably heard their early-1960s recording of the rock classic, “Louie Louie.” It won a Grammy Hall of Fame Award and Rolling Stone listed it as the fourth most influential recording of all time. It’s still played regularly on the radio, in movies, and on TV shows. The song is so popular because it’s intense and lazy at the same time, there’s an undeniable drive to the rhythm, a casual ease to the playing, and exuberant shouts in the background. It’s a good time. It’s a great song. And it’s not perfect.

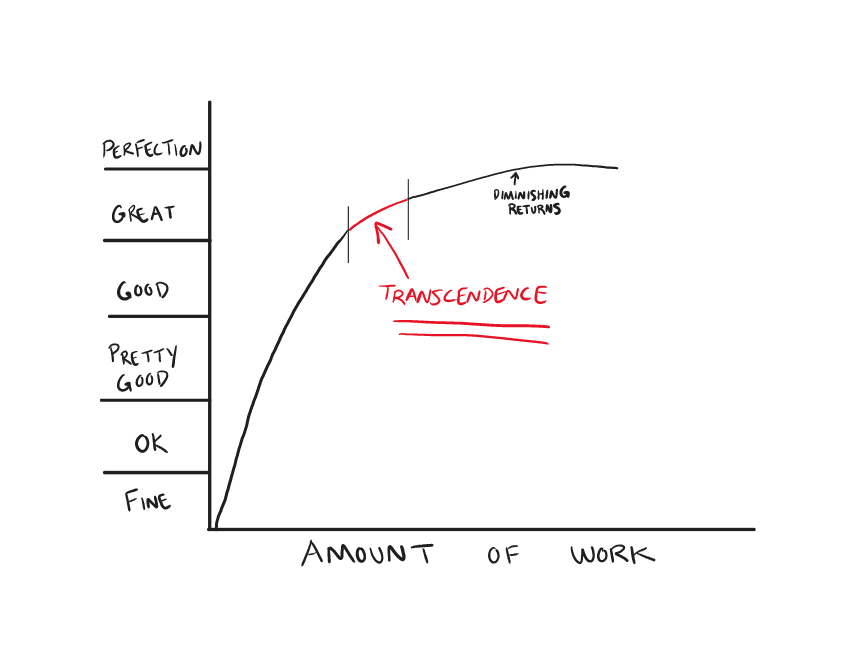

There’s a mistake on the recording—an obvious one. Following the guitar solo, singer Jack Ely comes in two measures early. After two halting words, Ely quickly realizes his mistake and stops short. The drummer also notices and adds an extra fill to lead the band back into the verse. If you listen closely you can even hear someone yell “fuck!” in reaction to the mistake. Today, this kind of mistake would be relatively simple to correct using sound studio software. “Louie Louie,” however, was recorded in just one take in 1963. We like to imagine the conversation that happened after the tape stopped: “Jack screwed up. Do we do it again?” Maybe it was the constraint of the fifty-dollar fee they had scraped up to pay for the recording. Maybe they felt they couldn’t get a better take. Or maybe it was something else. But we’re betting someone responded, “Nah, it’s good enough.” And, it was good enough. “Louie Louie” is transcendent. When you hear it, you’re not noticing individual instruments or technical musicianship, much less a blown bridge into the verse. You probably never noticed someone yell an obscenity. Why? Because you’re feeling the song, probably dancing or singing along.

When working on a creative project, you can make endless progress toward perfection. Think instead of the Kingsmen: look for the point of diminishing returns and move on, because that point is often also the point of transcendence, where the imperfection makes it better than perfect. This point isn’t always clear, but we can train ourselves to step back and recognize when what we’ve done is good enough. The Kingsmen didn’t get caught up in perfection. And they reached a different kind of greatness through being “close enough for rock ‘n’ roll.”

Abandoning the search for perfection doesn’t mean being satisfied with the first take (we can’t all be the Kingsmen, eh). Multiple sketches are critical for working out our ideas. But just as each sketch is necessarily imperfect, so will be the culmination of our creative process: our final piece. We need to work on it and work on it, but at a certain moment we need to let go. Picasso made forty-five sketches before he went to the canvas to paint his political masterpiece Guernica—but he didn’t make 450. He researched, sketched, evaluated, but he also knew when it was time to produce. In order to have maximum political impact, his painting had to be done in time to be shown at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1937. In the last draft of his painting Picasso changed its composition, raising the head of the horse that had lain in a heap on the ground so that it screams up into the sky, creating one of the most iconic details of the painting. Picasso knew it was good enough, and the result was transcendent.

Time: 10 minutes

Because we often strive toward a standard of perfection which can impede our creativity, and even stop us in our tracks, we sometimes need to force ourselves to be imperfect. That’s the point of this exercise.

1) Think about the issue you’re interested in working on.

2) Set a strict time limit: ten minutes.

3) Come up with ten (yes, ten!) ideas for art activist pieces that address your issue. Write them down in your sketchbook.

Look closely at what you have written down. It is impossible to come up with ten perfect ideas in ten minutes . . . which is why we had you try. Now, let’s work with your imperfect ideas. We bet a couple of them contain at least a kernel of something good. Try developing one or two toward completion. This is one of the ways creativity works.

It’s not always easy to follow the steps of the Art Activist Process Model. We’ve covered some of the common mistakes made by people who want to use the AAPM in their own art activism campaigns. To be effective art activists, we have to (surprise) practice this process to get good at it.

It takes humility to acknowledge that we don’t know enough about our subject and to do enough research, but it takes self-discipline and courage to not get stuck in the habit of overdoing research. Likewise, just as we sometimes over-emphasize research, we sometimes fall into the trap of overemphasizing sketches because it feels comfortable. There comes a time when we need to stop doing strategy meetings and roll up our sleeves.

At the same time, some practitioners grow tired of the planning stage and under-emphasize evaluation. They do this because they just want “to get after it.” While this gitt’er done attitude has its place, it can also be an indication that you lack maturity and patience. Without adequate evaluation, your plans will likely fall apart. Hope is never a substitute for sound planning. On the other hand, we can sometimes be too critical by over-emphasizing evaluation and being too critical. This is dangerous because it stunts our creativity. Sensing the balance between the two extremes is difficult to master – even for the most experienced creative people. Practice makes progress here.

Then there’s the danger of under-emphasizing action. Ultimately, the purpose of a project is the outcome. It’s fun to develop a project, but it takes a lot of hard work to execute it. This includes working late at night and for long hours. There will be many challenges along the way, such as not being able to find the right materials or people getting sick. Expecting these challenges ahead of time will help you stay on track and be successful.

And we mustn’t over-emphasize action, either. There are many reasons why people might want to finish a project quickly, even if it means sacrificing quality. Maybe there’s a deadline, or maybe people are getting frustrated and just want to be done. But all the steps of the creative process need to be well balanced in order for the final product to be good. Creativity needs time and space; if you rush through the process, the end result will be an uncreative mess.

Finally, a big mistake art activists make is not doing the stages of the creative process in order. If we do the stages out of order, we might end up with crappy ideas. We could put ideas out there that are not ready yet and they would probably fail. We can move back and forth between the stages: if a sketch does not pass the evaluation stage, we need to do more research and sketching before moving forward again. But even though we can move back and forth, it is still best to follow the stages in order. This diligence and professionalism takes effort, but in the end, it’s worth it. As Robert Browning said, “A minute’s success pays the failure of years.”

This article was adapted from Duncombe, Stephen, and Steve Lambert. The Art of Activism: Your All-Purpose Guide to Making the Impossible Possible. OR Books, 2021.

Other References:

Sharp, Gene. From Dictatorship to Democracy. Serpent’s Tail, 2022.

Beer, Michael, et al. Civil Resistance Tactics in the 21st Century. International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, 2021.

Popović, Srđa, and Hardy Merriman. CANVAS Core Curriculum: A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle: Students Book. Serbia, CANVAS, 2007.

Marovic, Ivan. The Path of Most Resistance: A Step-By-Step Guide to Planning Nonviolent Campaigns, 2nd Edition. International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, 2021.

Sholette, Gregory. The Art of Activism and the Activism of Art. New York, United States, Macmillan Publishers, 2022.

Clark, Howard; Garate. Handbook for Nonviolent Campaigns. Revised edition, War resisters’ International, 2022.

Thompson, Nato. Seeing Power: Art and Activism in the Twenty-first Century. Melville House, 2015.

Gavin, Francesca, and Alain Bieber. The Art of Protest: Political Art and Activism. Gestalten, 2022.

Miller, Matthew, and Srđa Popović. Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men, and Other Nonviolent Techniques to Galvanize Communities, Overthrow Dictators, or Simply Change the World. Random House, 2015.

Alinsky, Saul. Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals. Vintage; Reissue edition, 1989.

Bernays, Edward. Propaganda. Ig Publishing, 2004.

Abbott, Daniel. The Handbook of 5GW: A Fifth Generation of War? Amsterdam, Netherlands, Adfo Books, 2021.

Become a Member and enjoy a 10% discount at the Patriot Shop

Copyright 2023 © Patriot Propaganda. All Rights Reserved.